Warning: What Remains of Edith Finch Spoilers

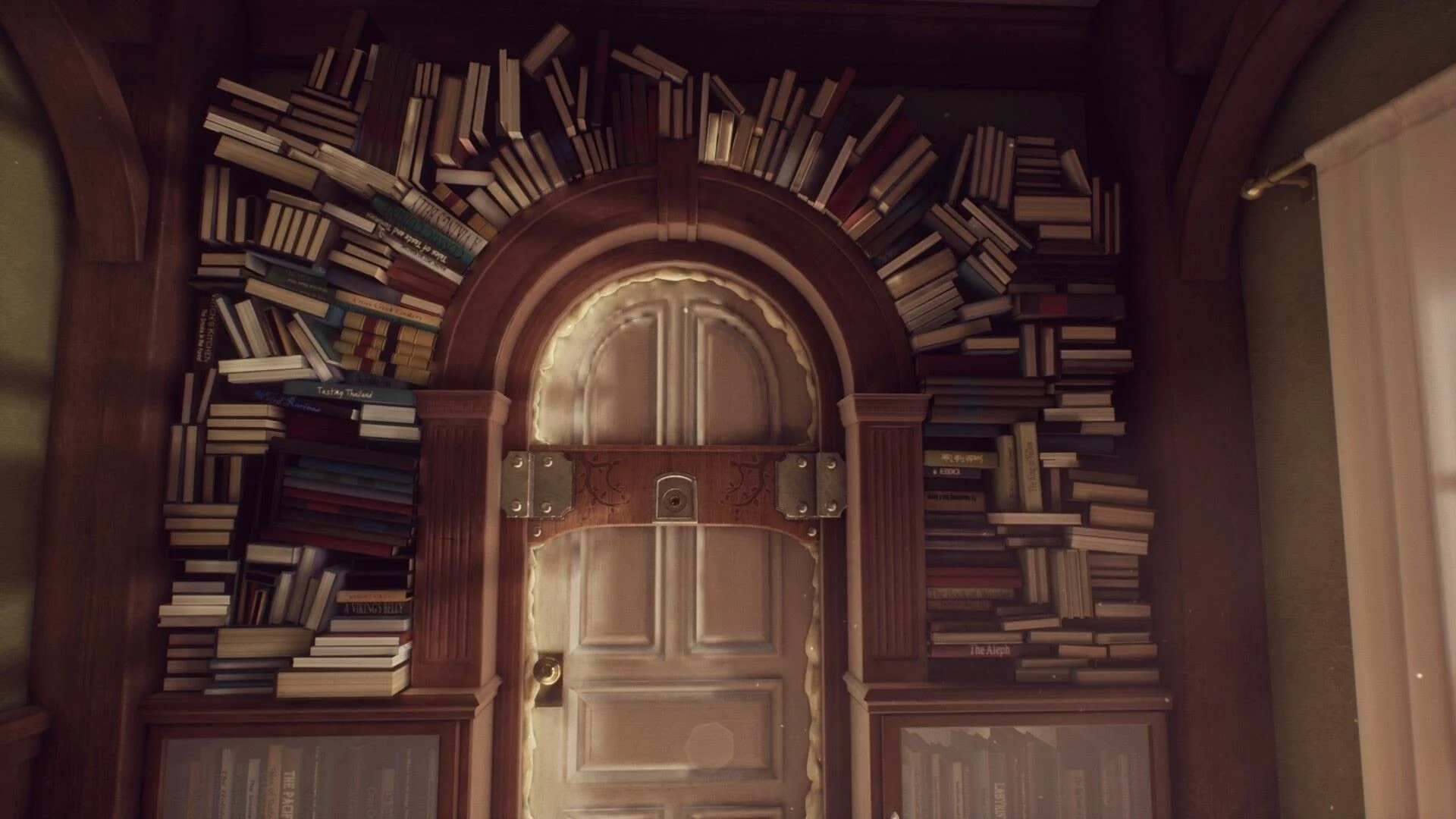

Playing What Remains of Edith Finch, one of the first details I noticed were the peep holes in each of the doors in the hallway. These allowed me as the player to peer into locked doors, to feel the tension of where I could be, but currently wasn’t.

I was so excited to see these peep holes. They gave me the opportunity as the player to imagine the inhabitants of the rooms before engaging with their objects and encountering their stories. When I saw them I thought about my mother describing her favorite childhood park as a girl: Enchanted Forest. Built in the same year Walt Disney World in Florida was built, Enchanted Forest in Ellicott City Maryland was a fairy tale themed park. It was ultimately a series of houses and characters from storybooks naturally embedded in the woods.

This park’s design was brilliant in two ways. The first was its integration in the woods, which made this seamless transition from reality into the extraordinary. Kids in Maryland are familiar with woods in their neighborhoods, but those woods can also hold Snow White’s house? And Cinderella’s castle? The houses looked so natural in these woods, as if you could go back home to your backyard and find a gingerbread man behind your swing set.

The second brilliant part of the design was the barrier it created between the child and the storybook figures. Most of the houses in the park were unable to be entered. Instead, there were only peepholes or glass windows for the children to look inside. From the outside, a viewer could only see a glimpse of these fairytale characters’ everyday life inside the house. For the three little bears’ house, a viewer could see: a fireplace, three beds with bedding, even a cartoon hunter’s head mounted on the wall of the three little bear’s house. If you were able to go inside you’d see the objects were not particularly extraordinary: the figures were paper mache; they didn’t move; the porridge in the bowls had never been touched and never would be. But from the windows, there was a magic of the unattainable. An invitation for the imagination to inhabit that space. To invent what it would be like to sit by the fire with Papa Bear, or to have a sleepover with Goldilocks. The fact that the actual characters were missing from most of these houses heightened the imaginative experience, requiring the park-goer’s mind to create their presence in that space.

You as the park-goer could see, but not touch—and that allowed for fantasy making. It’s amazing how the glass is more powerful than allowing the full exposure. From behind the glass, an otherwise ordinary cottage is made extraordinary.

Good writing and game design likewise never give all the answers, or all the things to touch. The great power of games is that they can literally give you that glass wall. They can let you touch, but not too much. They can allow your imagination to wander places your character physically can’t, which makes for an even more immersive experience.

I remember the energy that propelled me through the Legend of Zelda: Oracle of Ages and Oracle of Seasons was the unreachable places. I’d see a treasure chest across a body of water and wonder what was inside. I’d see Tingle on the roof of a building with a red hot air balloon and wonder who he was and how I could talk to him. I knew I would reach these things one day, that it was possible, but I wanted to know how. I imagined what it was like on the other side, what attached to a path going past the screen’s edges.

That tension gave me something to long after. It motivated me as a player to figure out how to cross over water, or what I needed to do to get to Tingle’s house. This idea of visual tension is common in many worldbuilding designs in video games. When we see an item beyond a hedge or body of water, we know it must be accessible but wonder how to get there. Breath of the Wild does this well through the visual height of the mountain surpassing any other landmarks on the terrain. It tells us as players that this place is important, and that we’ll go there, though if we attempt to go there immediately we’ll quickly realize we probably need to prepare more for the fight to come.

A particularly haunting example of this concept for me currently is the red overgrown door at the bottom of the town in Deltarune. The fact that we’ll have to wait quite a while until the next installment of Deltarune, as well as speculation from the strong theory community for Toby Fox’s games, makes this tension particularly great fodder for the imagination.

For this reason, as much as I wanted to love the peep holes in Edith Finch, they ultimately fell flat for me. What could’ve been a clever device to create tension between player and environment was in the end underutilized. Because we so quickly transition from room to room as players, the tension is too brief to be fully effective. If it was more difficult or time-consuming to get to some of these rooms--or perhaps some rooms were inaccessible at all--it would make the peepholes much more provocative. We’d rely on them to gather information, and draw conclusions about the former residents through the limited view of the peepholes. We’d also translate the content of the rooms differently than when we physically engage with each room. There are things we can examine up close that are impossible to ascertain from an outside view. But if this engagement was impossible, or limited, it could make the experience all the more interesting and effective.

That said, Edith Finch does allow through tension and speculation in another way: through surrealism in some of the character’s death mini-games. This surrealism is conveyed through literal content, but also visual design. It is information we gain, but have to translate. For some of the more surreal deaths, there are theories that try to translate these acts into literal, comprehensible terms. For example, with the worldbuilding of the physical terrain and story context, I have trouble believing Molly literally became a cat and a whale (whether this is or is not what the game developers intend), continuing to eat up the food chain until she dies. But it’s an interesting launching ground for us to speculate on Molly’s death. Through exploring her room, we are invited to eat unusual items, including toothpaste, holly berries, and gerbil food. This, along with her sequence of eating and transforming into larger and larger animals makes us wonder if she died from an eating disorder like pica. For Lewis, the visual design allows for tension between controlling Lewis’ imaginary reality while simultaneously controlling his literal reality: cutting fish. I still have no idea what to make of Barbara’s death, particularly in how it’s conveyed through the comic book panels and design. But I appreciate this room for speculation--it allows my mind to continue playing even after I’ve finished the game.

Even though this surreal tension allowed us to be in the thick of the action, it does distance us from reality, putting us less on the other side of a glass window and instead a funhouse mirror. The surrealism forces us to translate our actions and what we’re experiencing in a way that’s unusual for video games. Typically, we take our experiences at relative face-value in a game: we are this character, seeking to accomplish X objective, to obtain Y item. Games like Edith Finch however make us question the believability of our environment. The reliability of our narrator. Is this the literal death of the character? Or is this a metaphoric embodiment of their spirit, and how they would’ve wanted to die? These questions linger at the edge of our minds, like unopenable chests. They don’t allow us to learn everything from our gameplay experience, but to let the game linger in our minds for weeks to come.

Meg Eden teaches creative writing at Anne Arundel Community College. She has five poetry chapbooks, and her novel "Post-High School Reality Quest" is about a girl whose life is narrated as a text adventure game. Find her online at www.megedenbooks.com or on Twitter at @ConfusedNarwhal.