The final entry in this series of weird games is Eternal Poison (2008), a game which takes the boldest chances and reaps the least success of any of the three games I've discussed so far. In fact, I often refer to it as my favorite game that no one played. Eternal Poison is an extremely niche title (a Japanese Strategy RPG) with an inordinately high barrier to enjoyment in its initial phase. It features an over-abundance of complicated systems, demanding play mechanics, and a thoroughly baroque and obtuse set of requirements for advancing the narrative. Nevertheless, the revelations and structure of the second half of the game, especially the end-game content, remain my favorite of the past decade. Eternal Poison is a game that takes a lot of work to get into, but one that has perhaps the best and most rewarding payoff of virtually any role-playing game I've ever experienced. Be advised; this article will reference several of the most important revelations in the game's story, so anyone who was considering playing this complicated game from 11 years ago should expect spoilers.

I stated that Eternal Poison was an extremely niche title, and that assessment continues across several elements. Beyond being a Japanese RPG, a genre that relies on some very specific tropes and mechanics and which has limited appeal in the US as a result, it further compounds this niche status as a strategy-RPG. Strategy-RPGs use a grid mechanic to govern movement and attack, and while that gameplay can be deeply rewarding, there are few popular franchises in the US that implement this playstyle, outside of Fire Emblem, and perhaps X-COM. While the choice of genre alone would limit the potential of the install base, Eternal Poison further limits itself through the adoption of a gothic-noir aesthetic, which, like any other artistic choice, was bound to enthral some but alienate others. Essentially, the game made several artistic choices at the outset which continuously sliced the potential audience ever-thinner.

Yet, these choices are all of the sort that fall comfortably within the realm of artistic interpretation, and there should have been an audience for the game. Perhaps there would have been, if not for the increasingly complex layers of systems employed by the game. I spoke previously of the hurdles Baten Kaitos and God Hand placed in front of players, but there are insignificant in the face of Eternal Poison's choices. To begin with, the game has a triple narrative; however, even saying that is not a fully correct statement. In fact, the game has a quintuple narrative, but the fourth narrative is only revealed after completing one of the first three, and the fifth and final narrative can only be unlocked upon completing all previous narratives as well as the additional requirement of completing the game's monster compendium. Each of the three initial narratives has several branching paths, but in order to properly complete them, the player must choose the correct branches and complete several hidden objectives. The game gives no clear indication as to when the player has completed these objectives, and so achieving a "true ending" with any of the initial stories is extremely difficult without the help of an online FAQ.

Additionally, these requirements rely on the mastery of several of the game's deeply complex systems. As a strat-RPG, the game requires the manipulation of several units during combat. Each narrative provides two to four mandatory characters, as well as a surplus of "mercenary" units who can be recruited to your cause. Ten separate mercenaries allow you to round out your squad, but making the best use of them in order to clear each stage and gain necessary experience is certainly a case of trial-and-error. Once the player has refined their squad, they must move on to mastering other systems. There is a mechanic that allows players to capture monsters once they have been sufficiently weakened, and several "true end" requirements involve doing just that with specific enemies. Once captured, these monsters can be made to fight for your squad, or can be refined into a variety of weapons, items, skill points, or other perks. Knowing which monsters to keep or expend, and when to do such, is another matter where the player may be reduced to guesswork. Finally, the mandatory characters in each chapter are capable of changing their class at a certain level benchmark. This class change is permanent and irreversible, and affects all skills and statistics gained by the character from that point forward. Again, this is a case where moving forward without the aid of a FAQ can substantially hinder the ability of the player to complete the game.

The game sets up a very steep learning curve for new players, and an unforgivingly difficult set of circumstances for any player to advance the narrative, which is itself somewhat complex and offers a potential pitfall for new players. The demonic realm known as Besek spontaneously appears next to the kingdom of Valdia. Inside of Besek is said to reside the titular Eternal Poison, a sort of Holy Grail that can grant any wish. Three main protagonists attempt to learn Besek's secrets: Thage, a mysterious woman seeking the Eternal Poison in order to end the world; Olifen, a knight in search of a Princess who is said to have been kidnapped; and Ashley, a servant of the church. Whichever story is selected, the player must traverse through several layers of Besek, ultimately arriving at the throne of the Eternal Poison and facing the same final boss. Many players (myself included) were likely to select Thage's narrative first, as she was billed as the game's "main character" in artwork and press releases. Unfortunately, her story is by far the most bland, and her supporting characters by far the least interesting. The motivations for Thage and her partners are deliberately obscured until the finale of her narrative, and while there are some truly riveting revelations there, the time and effort needed to power through her otherwise uninteresting story arc meant that few players made it all the way through.

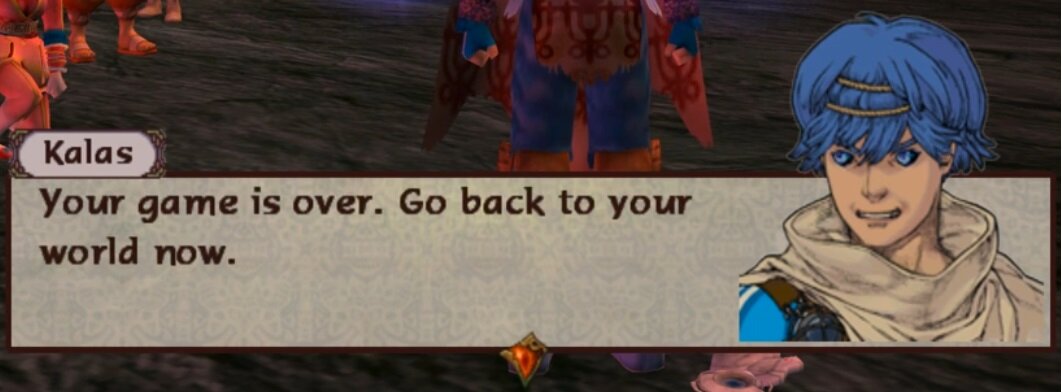

And once again, this is a shame, because the full narrative of Eternal Poison is one of the richest, fullest, most complex and most rewarding of any game I have ever played. The triple narrative of the first three stories interconnect in a number of ways, and playing all three leads to many discoveries about the world of Eternal Poison. Every narrative makes its way through Besek to the throne room of Castle Valdia, where the characters discover the king of Valdia attempting to awaken Izel, an ancient god. However, it isn't until Morpheus's tale is unlocked that the truth of the story begins to be revealed. All of the previous narratives occurred despite the obvious contradictions they entail. The reason is due to the power of Izel and the Echo of Time, which has caused Besek to reset and all previous events to be erased. Morpheus is able to break through the Echo of Time, however, at the end of his journey, it is revealed that Izel had manipulated all previous events to reach this point. Izel manifests in her monstrous true form, resulting in the main characters of all previous chapters being brought together for a climactic final struggle.

The above capsule summary does little, I think, to truly demonstrate the rewards of untangling the narrative oneself as the game is played through; however, it does allow me to illustrate one point. Each of the chapters is a standalone story, with each hero (or antihero, as the case may be) encountering struggles both internal and external, overcoming obstacles, forming bonds, saving allies, and reaching a satisfying happy ending. At the climax, however, all of that is rendered moot. The choices made, and the genuine, difficult effort put forth by the player to reach the "true endings" for each character are negated by the Echo of Time. The game is quite explicit; in the Final Tale, you do not save your friends, you do not save the princess, and there was nothing anyone could do to prevent this turn of events. Furthermore, it is also revealed that the goddess worshipped by the church, and in turn by the people of Valdia, is, in fact, the monstrous Izel. Nothing matters; everything is a lie. One might think that this devastatingly nihilistic approach to storytelling could be construed as an anticlimax. However, after navigating the byzantine requirements to reach the Final Tale, uncovering the truth behind the world of Eternal Poison actually feels incredibly rewarding. Paradoxically, negating the consequences of the previous playthroughs actually pays off the player's hard work in arriving at the end.

Ultimately, Eternal Poison is probably the weirdest of the three games I have analyzed in this series. When it comes to Baten Kaitos or God Hand, I was able to point out one or two significant flaws that negated player engagement in the early stages of those games, and which prevented mass audiences from discovering the potential that lay beyond. In the case of Eternal Poison, I am not certain there is anything that could have made this game a financial success. It's not merely a consequence of one or two elements that distract from the game's more marketable aspects; the things that hold back Eternal Poison are the core design choices that inform the entirety of the production. It is, undeniably, its own unique beast from start to finish. This may, in fact, be the reason it is my personal favorite of these three games. It took the biggest risks, and it never compromised on those visions. It was niche and difficult, and weird, and it did all of that without trying to be the next Final Fantasy or Dragon Quest. It was the game its designers wanted it to be; it was never going to be a game that everyone loved. That kind of conviction genuinely appeals to me as a player, although it's hard to say if that would still be the case if I didn't also fit comfortably into the exact niche audience that the game was made for. Nevertheless, I love all the little oddities that abound in Eternal Poison (and I never even had the time to talk about the townspeople, or the refugees, or the odd mini-game you had to play to unlock concept art), and the game ranks among my all-time favorites.

This concludes my look at weird games. Hopefully, through these articles I have been able to articulate why it is that I think these games failed to find mass appeal, but also why I think many people might have missed out on some wonderful experiences. As I said in the introduction to this series, I hope that you might be willing to take a chance the next time you see a game that looks a little atypical. Maybe you'll find that the developers took some chances, too, and maybe you'll find a game that you're still thinking about a decade later.

Dr. Daniel Gronsky is a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature and Cultural Science, focusing on media studies in film and video games.