I once jumped into a nearly empty dumpster to get a piece of scrap wood. I had just started learning woodworking after reading Nick Offerman’s Good Clean Fun. I spent my money on tools, which meant I couldn’t afford wood. I broke down pallets, collected scrap offered in Craigslist posts, cut IKEA bed slats to size, and yes, jumped in a mostly empty dumpster in ninety-degree weather. I seemed silly to my coworkers and friends, getting excited about free wood in my office parking lot. I wasn’t even trying to make something in particular. I was just excited by the potential of the materials. My real-world behavior was eccentric, to put it generously, but now I notice how often games have us similarly gather and repurpose other people’s garbage through crafting. I’ve made a toy from a tire in Animal Crossing: New Horizons. I’ve fashioned explosives from an old tin can in Rise of the Tomb Raider. I’ve built underwater bases from scrap metal in Subnautica. We’ve all done it for years. In my favorite game Mega Man Legends, I gave Roll Caskett, Mega Man’s mechanic, a blunted drill to create to create the “Drill Arm”—it’s exactly what it sounds like—and I used it to explore the underground ruins of Kattelox Island. It may seem like a tenuous connection. The crafting systems in all four games have obvious differences, but if we focus on something as specific as how each game uses garbage as a material, we can give texture to the mechanics. The rewards structure in each game hints at the different player interactions they value, and after reflecting on these systems, we may even feel differently about the things we make in real life.

“He loves to make up stories to help deal with his environment” - Max’s Autistic Journey

So…Autism is…an RPG?

That was the first thought I had when watching gameplay footage of Max’s Autistic Journey. At first, I found the analogy problematic and troubling. But then the more I thought about it, the more it grew on me.

Now that COVID restrictions are finally lifting, and travel once again becomes possible, I've been reflecting on how I spent approximately the last 18 months. I consider myself a fairly accomplished traveler and have been fortunate enough to see a good portion of the world. When, like everyone else, I was restricted to my home, I turned to video games to scratch that itch for travel and exploration. Yet, while both may be enjoyable, it is clear that those are obviously not equivalent experiences. Fantastic worlds, no matter how rich and rewarding, don't have the same flavor as getting to see new parts of the world one actually lives in. However, I was surprised to find that there were some games that did manage to recreate a measure of that feeling - games that take place in real locations where I've actually been.

Legend of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds has been on my list to play for quite a while, but only during the 2020 quarantine did I finally have time to pull it out again. This game reminds me why I fell in love with Zelda games in the first place. There’s no Navi, following you around. It’s good old-fashioned exploration, and kinesthetic and environmental learning.

Being stuck inside the house during quarantine, I wanted to escape. I wanted to see any landscape other than the one out my window, in my yard, or down the small stretch of street that was safe for us to walk each day. Unable to wander and explore outside, I fell into the Hyrule and Lorule of A Link Between Worlds. I looked for every bottle, every heart container, and every Maimai. I hadn’t been this much of a completionist since my Donkey Kong 64 days.

“...some people never stop

They're always moving on”

I listen to CG5’s remix of “Weird Autumn” on loop, and have been doing so for the past 2 years straight. Something about the song compels me, the same thing that makes me continue to return to the game it originates from, Night in the Woods. I find the song fascinating in part because we never hear about this character Weird Autumn anywhere else. She only exists in this song in the background of a mini-game: as someone who disappeared; who is “weird;” whose house in her absence remains empty, abandoned and “weird.” I’m haunted by the idea of Autumn: who she is, and what was “weird” about her. I’m also haunted by that idea of time: of someone being there one minute, and gone the next.

Noah Caldwell-Gervais has been called “the Closest Thing Video Games Have to Roger Ebert,” but I don’t get the sense that he’d be entirely comfortable with that comparison. Despite seven years of experience making longform video essays, he doesn’t view himself as an authority of any kind.

He’s best known for doing long videos covering entire franchises. His video “The Complete Call of Duty Single Player Campaign Critique (For PC),” for example, is just over two hours long. These long, holistic essays allow him the chance to contextualize whole series in a way that just wouldn’t be possible in a short-form video, and it gives him plenty of space to show off the distinct voice he’s developed.

Critical Distance interviewed Noah about his process a few years ago and rather than repeat their discussion — which I recommend checking out — we jumped around. Below you’ll find some excerpts from our conversation, edited for length and clarity below.

Why we play difficult games and what keeps us coming back.

Warning: Heavy spoilers for The Dark Pictures Anthology: Little Hope

Ever since The Dark Pictures Anthology: Little Hope came out in October 2020, it’s received harsh criticism from gamers and reviewers alike. Most of the complaints I observed revolved around the speed of the quicktime events, the ineffective nature of the multiplayer mode (in contrast to Man of Medan), and most of all the narrative’s ending.

I’ve long held a fascination with “so-bad-it’s good” entertainment. From childhood viewings of Mystery Science Theater 3000 to internet critics like James Rolfe and Joe Vargas who came to prominence in the mid-2000s, the media I’ve consumed has helped foster an ongoing love of the unbelievably bad, the films and shows that manage to miss the mark by such a wide margin that they somehow loop back around to a dubious form of success. And, as a gamer, I’m a huge fan of video games that fall into the “so-bad-it’s-good” category.

Many Pokémon players will jokingly quote Professor Oak’s memorable phrase: “Are you a boy? Or are you a girl,” the first question asked of players when beginning a new save file in all Pokémon games following Pokémon Crystal. While the language is stilted and the trope memorably comical, this question provided a novel phenomenal choice for me as a new gamer in 2001.

Chris Franklin is a game designer and critic best known for producing the web series Errant Signal on YouTube. He’s been making videos about games for over eight years, and in that time, he’s developed a style that’s both academic and casual. His videos are often holistic close reads, exploring the narrative and mechanical themes of a game and drawing conclusions about what a game is trying to accomplish, but his videos have also covered design concepts and games criticism history. In 2019, he started Errant Signal: Blips, a video series about overlooked, small independent games.

Chris and I talked about the process of writing about games, the challenge of defining a “small” game, and the times he has made mistakes in his analyses. Below we have some excerpts from that conversation, which have been edited for length and clarity. If you’re interested in hearing everything he and I discussed, you can download the full audio below.

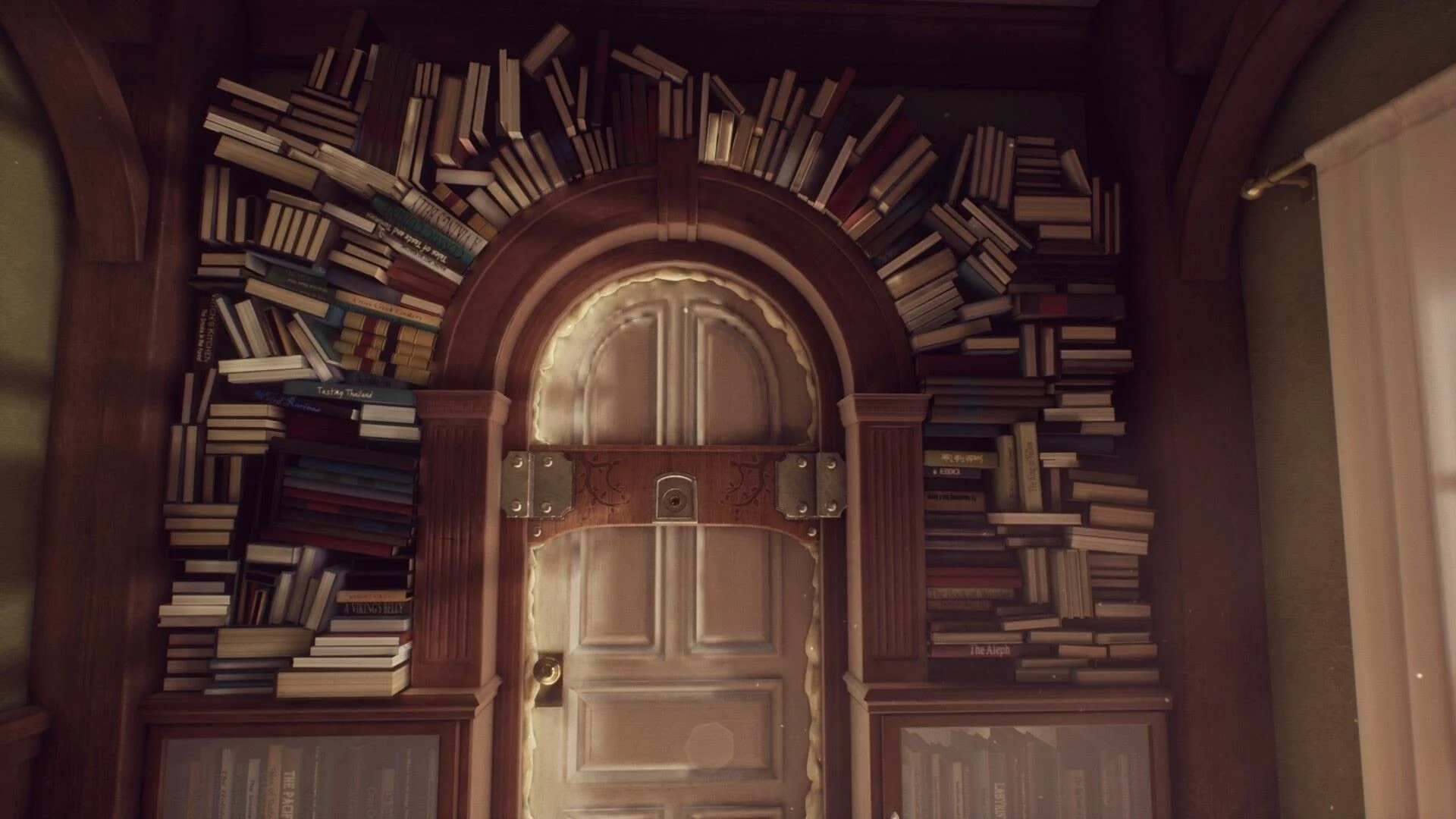

Playing What Remains of Edith Finch, one of the first details I noticed were the peep holes in each of the doors in the hallway. These allowed me as the player to peer into locked doors, to feel the tension of where I could be, but currently wasn’t.

I was so excited to see these peep holes. They gave me the opportunity as the player to imagine the inhabitants of the rooms before engaging with their objects and encountering their stories. When I saw them I thought about my mother describing her favorite childhood park as a girl: Enchanted Forest. Built in the same year Walt Disney World in Florida was built, Enchanted Forest in Ellicott City Maryland was a fairy tale themed park. It was ultimately a series of houses and characters from storybooks naturally embedded in the woods.

The final entry in this series of weird games is Eternal Poison (2008), a game which takes the boldest chances and reaps the least success of any of the three games I've discussed so far. In fact, I often refer to it as my favorite game that no one played. Eternal Poison is an extremely niche title (a Japanese Strategy RPG) with an inordinately high barrier to enjoyment in its initial phase. It features an over-abundance of complicated systems, demanding play mechanics, and a thoroughly baroque and obtuse set of requirements for advancing the narrative. Nevertheless, the revelations and structure of the second half of the game, especially the end-game content, remain my favorite of the past decade. Eternal Poison is a game that takes a lot of work to get into, but one that has perhaps the best and most rewarding payoff of virtually any role-playing game I've ever experienced. Be advised; this article will reference several of the most important revelations in the game's story, so anyone who was considering playing this complicated game from 11 years ago should expect spoilers.

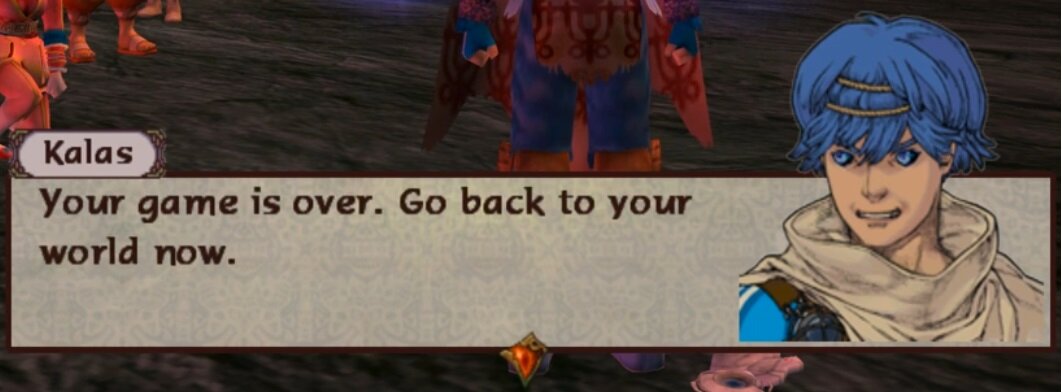

In my introduction to this series, I suggested that a weird game is one that fails in an interesting way. Make no mistake; Baten Kaitos: Eternal Wings and the Lost Ocean (2004) is a weird game. Even though it falls readily into standard JRPG tropes, it makes numerable fascinating choices that are likely to grab a novice player's attention before the end of the introductory sequence. For instance, the game is set in a world above the clouds on a series of floating islands, the oceans having disappeared eons ago in a climactic struggle with an ancient evil. The people who inhabit these islands are winged, with the exception of our main protagonist. Having been born with only a single wing, he must make do with a prosthesis, a fact that opens him to discrimination and makes him bitter toward the world around him. These are themes and concepts seldom observed in other titles, and offers a bold take on standard JRPG fare.

In the previous installment of my weird games series, I discussed Baten Kaitos, beginning with the overall positive first impression that game left on me. There was a lot to like out of the gate, before frustrations with some of the game's more novel design choices might lead a player to abandon the game. God Hand (2006), on the other hand, so to speak, has overwhelmingly negative first impressions. The backgrounds are hideously unfinished in tones of gray and brown, and despite being a third-person brawler, the game saddles the player with tank controls for movement and an extremely limited field of vision, fixing the camera directly behind the player character. I imagine many players did not last more than 15 minutes before throwing in the towel, which is a shame, as like the other games in this series, God Hand is a game with more than might meet the eye at first glance.

Let's take a moment to talk about "weird" games. You know; the ones that don't necessarily sell very well, that might not be as polished, or honestly even as "fun" as some better known titles. The ones that have both enthusiastic fans and severe shortcomings. What is it about these games that sticks with people, even when these games fall far short of the benchmarks for success in the industry? What is the place of these oddities and artifacts? Over my next three articles, I hope to share with you some in-depth examinations of three of my favorite video game oddities: Baten Kaitos (2004), God Hand (2006), and Eternal Poison (2007).

Fire Emblem is one of my favorite franchises and is a series I continually return to as a stress-reliever. Fire Emblem: Three Houses in particular has a compelling framework that’s allowed for some interesting reflections on my own personal coping skills as well as models for how to strategically cope in the everyday. Namely, Fire Emblem: Three Houses is about strategically managing limited resources.

Animal Crossing: New Horizons just came out, and in writing this, it’s been a little over a week since the coronavirus threat hit the US and social distancing became a way of life. Most of my spring calendar has been eliminated, and as someone whose structure was largely built from those events, I’ve found myself simultaneously listless and anxious, not knowing what to do with myself and unable to do much in the way of normal work.

As someone who is always interested in stories, and in particular the ways in which video games attempt to tell stories, I made special note of all the various panels at the 2020 MAGFest event with a narrative focus. The first day was packed with such panels, including "Games as Story Machines" and "Layering Leitmotif: Telling Stories Through Musical Ideas." But the panel that most captured my attention was "Playing With Your Stories," presented by Dillon Chan.

In recent years, with the explosion of mobile games and the broadening of platforms such as Twitch and esports leagues, it’s become clearer than ever that gaming is a medium for everyone. Though some “hardcore” gamers might grumble about this, the fact remains that gaming is made richer and better the more inclusive it becomes. However, there’s still a way to go before that inclusion and representation reaches where it needs to be, especially at the level of everyone even being able to play and enjoy games.